Personal Diary: Growing older as a new Canadian

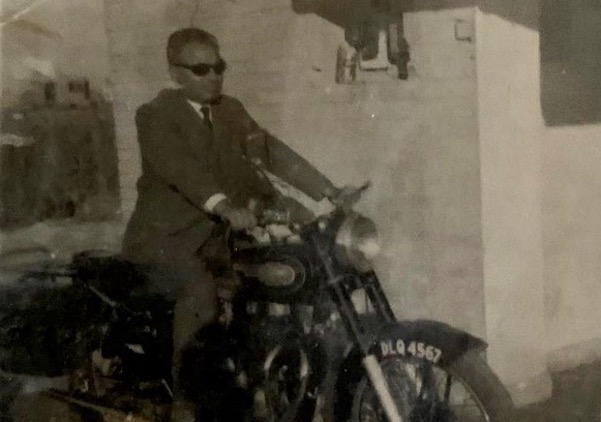

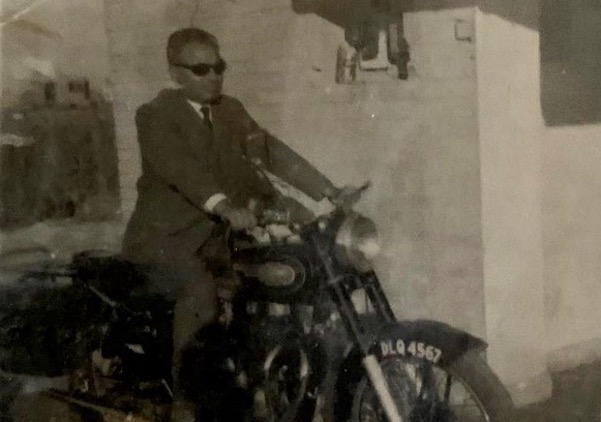

Dev Dutt Sood, grandfather of author Jayshal Sood, riding a bike in India, circa 1950

My first immigrant experience as a teenager lasted only four months. My family moved to the United States in 1996. Our Green Cards were sponsored by my grandfather Dev Dutt Sood, who had arrived in 1985, in Lynchburg, Virginia, after retiring from public service as an Executive Engineer at the Irrigation Department in Punjab. His permanent resident petition was filed by my aunt, who had gone to the US nine years earlier. After he became a US citizen, Grandpa Sood filed for Green Cards for my dad and uncle.

By the mid-1990s, grandpa had moved to Orlando, which is where we arrived. However, unlike grandpa, who thoroughly enjoyed his sunset years in central Florida, my dad felt miserable upon our arrival. Dad, who ran a reasonably successful business in Punjab, was just not prepared to start his life from scratch. Adding to his misery was the culture shock he faced in the US.

He decided to move back to India after a mere four months in America. The bait for me, a 10th grader at that time, to return to India was an offer from dad to buy a new motorbike — the same make as in the above photograph — as soon as we landed in India. I took it, though the motorbike did not come until I started college.

Now, as I settle and integrate, along with my family, in Canada, my dad’s decision to give up US permanent resident status still perplexes me, even though I perfectly understand why he chose to do so. Twenty-five years down memory lane, I also try to understand how my grandfather would have felt about my father’s decision. I rationalize the different experiences of three different generations of immigrants within my family — my grandfather, father, and myself — as examples of intergenerational decision-making among immigrants.

Beyond the horizon

In the next decade after returning to India from the United States, I completed my undergraduate education, met my better half, and set sail for the US again. This time, however, I traveled not as a dependent immigrant, but as an international student with a prestigious scholarship at the American University’s School of Communication. For someone in his mid-20s, it was mainly an educational adventure in media technology and news reporting. No other thought occurred to me at the time. I was content that I had it all with the acceptance letter from a top school in the US capital.

READ: Ignatius Chithelen: Peeling the layers off the Indian immigrant experience and more (January 31, 2019)

There is an old saying that change is the only constant and it was to dawn upon me soon. With the school’s stress on ground reporting, I hit the ground running, covering local elections through multimedia in the first week of landing in America. “A communication degree with a specialization in broadcast journalism. How could I have missed the implications of my distinct Indian accent,” I ask myself today. The instructors at the school underscored reporting facts, figures and data, and I vowed to refrain from reflections and opinions in all that I wrote from thereon.

The next few years brought about significant changes in my life, but at the time I was unaware of what richness and learning awaited me. I wrote for various reasons, and the writing of the times dropped hints of a transition I was undergoing: from shorter pieces to longer ones, and from plain facts to storytelling. Inadvertently, I was gravitating closer to my purpose. I was now covering immigrant stories and my writing shifted focus from the preconceived storyline to the behind-the-scene process. In other words, from immigrant success to the immigrant experience.

Seeing through acquired age

The older immigrants I interviewed were keen on sharing their rags-to-riches, larger-than-life success stories, and their newcomer struggles. I was all ears, not due to a brilliant strategy but because I needed to gain the immigrant experience to contribute to those conversations. My soft, developing mind identified new leads and off leads, and there was a sense of accomplishment in this unique ability to winnow insights and wisdom from raw, undirected conversations. I was now more bent toward understanding mindsets that led to aseemingly common pattern among immigrants: staying put against odds, participating in media and politics, giving back to the communities, acknowledging diversity, origins and belongingness, and revisiting their cultural roots after investing decades learning and adopting etiquettes of their new countries. The shared experiences stayed with me and triggered new learning avenues.

READ: Religiosity, humane words help Americans empathize with immigrants: Study (January 7, 2016)

Learning and unlearning

By the time I reached middle age, I had developed a genuine curiosity to learn from those who were there before me, irrespective of their immigration background. My respect for age increased, along with my patience to listen to longer responses that seemed off-topic at the start but made sense as I delved deeper into the conversations. Although a tougher route, I feel that an acquired skill is better than a gifted or natural skill, as the acquired one comes through a learning process. A gifted skill could make a person lack empathy and connection with lesser mortals who have struggled to acquire that skill.

The unlearning part, too, is a natural and essential outcome of age. This point was anchored during a casual conversation with a cameraperson from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), who had retired after dedicating 40 years to news production. He told me how in retirement he was trying to unlearn all that he took pride in during his work years. The takeaway was a need for decompression to imbibe new life skills, this time, for “retirement.”

Changing perspectives with fleeting years

As I integrate into Canada, I have a greater understanding of multiculturalism and inclusion. The openness of mind has enabled the realization that our impressions of others can change when we understand that people are multidimensional. Knowing the unknown is impossible, but allowing others to express themselves with freedom from judgment could discover an unchartered common ground to develop opportunities for effective synergies. Apparent incompatibilities due to outer appearances, accents, or physical ability could be a barrier to effective communication, however, awareness and genuine interest in everyone’s well-being can overcome this barrier leading to a deeper connection that communicates beyond race, appearance, or language.

READ:Indians making Canada new home doubles in 2019 (February 19, 2020)

This realization has provided the strength to give stakeholders space to express themselves professionally and personally. I have purged my reading-between-the-lines inclination. Most of us fall somewhere between good and evil, and I now follow the middle path approach — allowing people to convey their persona and true character over time. The accents, both mine and of others, are no longer a barrier, baits do not divert and a motorbike does not throw me off the track anymore.

The two most important days of our life are the day we are born and the day we discover our purpose. While the birth was beyond my control, the purpose revealed itself through immigration and age.