Indian Americans are rising in American politics due to Civil Rights Movement

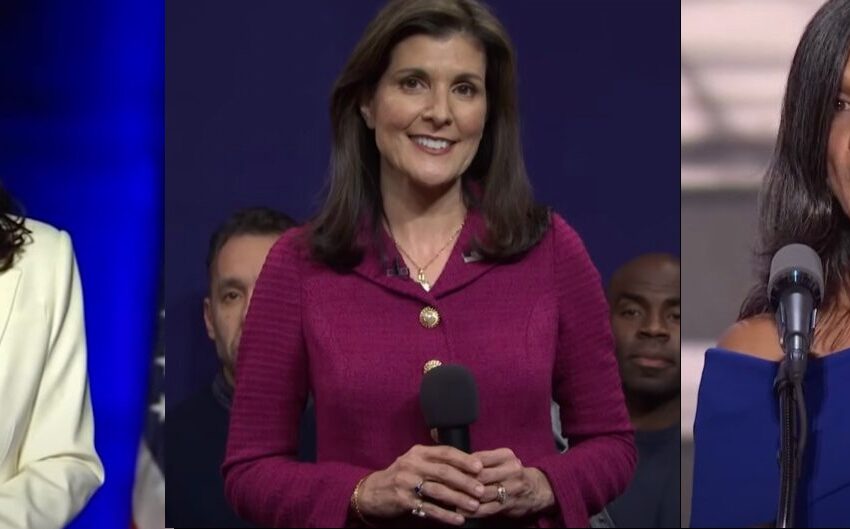

Kamala Harris (left), Nikki Haley (center) and Usha Vance

As Kamala Harris and Usha Vance take the political stage as the Democratic presidential nominee and the spouse of Republican vice presidential candidate, two Indian American activists suggest the community owes its rise to Black struggle and the Civil Rights Movement.

“Expect to hear a lot about Indian American success stories throughout the 2024 election season,” write Reshma Shamasunder, executive director of Asian American Futures, and Rinku Sen, executive director of Narrative Initiative, in an opinion piece in the San Francisco Chronicle.

“Narratives about Indian American exceptionalism, high levels of education and successful integration are bound to come up repeatedly,” they write. “But there’s another story to tell: …how Black struggle and the Civil Rights Movement enabled our families to make our homes in America.”

“Indian Americans have rapidly been climbing the political ranks. In 2013, there was just one Indian American in Congress and less than 10 in state legislatures. Today, there are five Indian Americans in Congress and nearly 50 in state legislatures,” Shamasunder and Sen noted.

“It is easy to credit their successes to the myths that have prevailed historically, and which are currently being bolstered by many in the mainstream media, depicting Indian Americans as having prospered due to sheer will and hard work,” they write. “But this incomplete telling of our rise erases the complex history of how our communities arrived in this country and why we have thrived.”

Small numbers of Indian immigrants, primarily Sikh farm workers who migrated to California, arrived as early as the late 1800s, but further immigration was soon prohibited by the Immigration Act of 1917, which “barred all immigrants from the Asiatic zone” from entering the United States — itself an expansion of the 1885 Chinese Exclusion Act, the two recalled.

“It would take nearly 50 years for the discriminatory policy to be dismantled by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which put an end to quotas and outright bans against Asian immigrants,” they write. “But the act, which largely was a result of the ongoing push by Black and brown communities for civil rights, came with some constraints.”

“While Indians were now allowed to immigrate, the act privileged highly educated and often upper-caste professionals who spoke English,” Shamasunder and Sen write. “As a result, our people may have arrived with few bags and little money, but they had the social and economic positioning to enter America’s bootstraps culture with advantages not accessible to Black people and other communities of color.”

“That legacy continues to this day: As recently as 2021, 80% of all Indian immigrants held at least a bachelor’s degree compared to just 13% of US born adults,” they noted.

“Because it’s not often talked about within our communities, many Indian Americans don’t realize how deeply we benefited from the Civil Rights Movement and the fierce organizing of Black and brown leaders,” Shamasunder and Sen write. “By the early 1970s, the Civil Rights Movement had outlawed racial discrimination in American institutions and established new practices such as affirmative action to correct inequities.”

But “a half century later, we’ve seen a conservative-leaning Supreme Court gut the landmark 1965 Voting Rights Act, strike down the right of colleges to use affirmative action in their admissions processes, and overturn abortion access.”

“At a time when the unfinished agenda of the Civil Rights Movement is under attack and the freedoms we cherish are at risk, the widespread characterization of Indian Americans as rugged individualists pits us against other communities who have faced marginalization for generations and glosses over South Asian American communities who face poverty and other barriers,” Shamasunder and Sen write.

“This narrative also willfully neglects the majority of Indian Americans who stand for politics of inclusion and diversity,” they write. “Indian Americans, who like other communities of color face racism and discrimination, remain overwhelmingly committed to policies that invest in people and communities of color, including more expansive immigration laws, stricter gun control laws, and better access to educational opportunities for Black people and people of color.”

“Once they dig into this history, many Indian Americans can and do reject being positioned as pawns in racist narratives against Black and brown communities whose organizing and resistance enabled our families’ immigration, our education and our livelihoods, now and into the future,” they write.

“By embracing the legacy of racial justice from which ours and other communities have benefited, we can help open the door to opportunity for coming generations, and continue the important work of dismantling racial discrimination, not just for us but for all people of color,” Shamasunder and Sen concluded.